February 8, 2016

Operational Models and Educational Debt in ATS Seminaries

Why do we care? What do we know? What can we do?

The Glaring Omission

Often times, the challenges we face and the opportunities they create are multi-faceted. The fact that large numbers of seminarians are taking significant amounts of educational debt with them when they graduate is no exception. In a recent research project that was part of the Lilly Endowment’s Economic Challenges Facing Future Ministers initiative, Dr. Harriet Rojas and I found that theological education may need to address areas related to operations, educational models, market awareness, and curriculum if it is to have any impact on student debt.

Last week, we continued a discussion on why we care about this topic by looking at how much debt is too much debt and how we may be enabling students to borrow more than they should. This week, we bring to a close our conversation about why we care by addressing a glaring omission.

When I first thought about this research project, I must admit my thoughts were rather biased. Based on previous research I had conducted, it seemed that seminaries were doing a disservice to students because they were dramatically increasing the price of tuition. This increase was related to the fact that the cost to deliver theological education was rising dramatically. My goal with this research project was to shed light on the operational and educational assumptions that are present within theological education and possibly challenge some long-held assumptions. My thought was if we can decrease the cost to deliver theological education, we can lower the price of tuition and thereby lessen student debt loads.

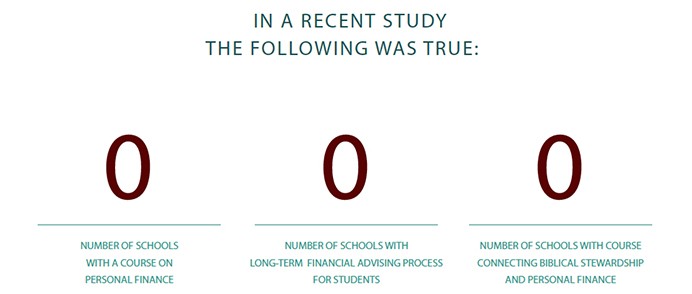

While this research project did surface a few things that should cause us to look closely at the assumptions we make, it also shed light on another equally disconcerting issue. We have a glaring omission in our curricula; an omission that seems to be present at higher education institutions across the nation and across sectors of the industry. It was certainly absent at each of the seven schools we studied as part of this research project.

No school in our study is actively working with its students in terms of financial planning, debt management, or personal finance. While all students have to go through entrance and exit counseling in order to receive any federal student aid, we do not require students to think critically about the amount of loans they are using to pay for education. In some cases, we have face-to-face conversations with students and in other cases, we try to make them understand how much aid they are really taking. However, no school in our study has a required course in the curriculum that deals with personal finance.

Why is this important? The school in our study whose students graduate with the lowest levels of debt was not the school with the lowest price of tuition. As we pointed out last week, because of the way federal aid works students are able to borrow large sums of money, even if they have a 100% tuition scholarship! While lowering the price of tuition will help to lower the amount of debt incurred by students, it will not bring wholesale change.

If we hope to have a lasting impact on the issue of student debt, we must begin to find ways for conversations about personal finance to become required components of the curriculum at our schools. This is a stewardship issue, which means it is a theological issue. We cannot expect our students to think critically about student loans if we are not asking them to do so. Our society is the first in human history to figure out how to live on $1.10 when our income is only $1.00. By omitting this requirement from our curriculum, I fear we are enabling a future of poor stewardship.

I must thank Dr. Rojas for being the driving force behind finding the data that revealed the schools in our study were not integrating these conversations at their institutions. Her personal research into student debt revealed that students who participated in a personal finance class were much more prepared to understand their federal student loans.

In order to help schools and churches begin to address this issue, we created a partnership between Sioux Falls Seminary, Indiana Wesleyan University, Northern Seminary, The Ron Blue Institute, Asbury Seminary, Ashland Seminary, and Generosity Monk. Together, we are going to publish a 12-week curriculum that will provide biblical truths, spiritual guides, and practical examples of biblical stewardship. Once published, it will be given as a free gift to all seminaries in the Association of Theological Schools. The curriculum can be packaged as an undergraduate, master’s level, or doctoral level course and will include a handbook and videos that can be used by instructors.

We need to address this glaring omission in our curriculum. When we couple that with changes to our educational and operational models, I believe we will begin to see a lasting impact on the student debt issue facing theological education.

Come back next week as we begin to look at what we know from our research on this topic. We will share a new infographic and an interesting piece of data about debt and tuition prices.