February 15, 2016

Operational Models and Educational Debt in ATS Seminaries

Why do we care? What do we know? What can we do?

Part One: What Do We Know?

Today, we continue a series on operational models and student educational debt at seminaries within the Association of Theological Schools (ATS). Over the last few weeks, we looked at why we care about this topic. Today, we are going to share a little more about what we know to be true regarding operational models and student educational debt. Our assertions are based on data published by Chris Meinzer, Senior Director of Finance and Administration at ATS, and information gathered during a joint research project conducted by Sioux Falls Seminary, Northern Seminary, and Indiana Wesleyan University.

The staggering levels of educational debt being incurred by many seminarians across North America are worth noting. The number of students graduating from seminaries having incurred over $30,000 in educational debt while in seminary has increased by nearly 300% since 1996. Some believe this is primarily the result of the astronomical increase in tuition prices at seminaries. Indeed, since 1993 the price of tuition at ATS schools has risen at a rate that’s nearly three times faster than the rate of inflation. While this is cause for concern and should be addressed, it does not seem to be the single driving force behind the higher levels of student debt. We discussed this reality a few weeks ago. The graph appears again in our latest infographic.

When we discovered the lack of correlation between price and debt levels, we turned our attention to other possible causes for the rising levels of student debt. As it turns out, the increased access to credit created by changes in the federal student aid program and the amounts that schools include for various components of the Cost of Attendance may be enabling students to borrow more than is needed. Our post two weeks ago covered this in some detail. Put simply, we (like most of higher education) have created a system wherein even students receiving a 100% tuition scholarship can borrow the maximum of $20,500 each year in federal loans.

So let’s move on to what else we know from our research.

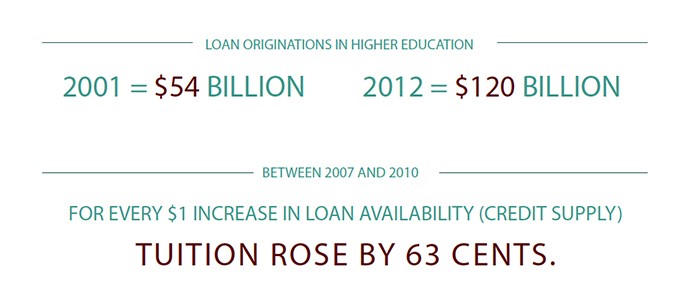

If students have access to increasing levels of funds through debt, we wondered, how might this be connected to rising tuition prices? Fortunately, we were not the first to ask this question. David O. Lucca, Taylor Nadauld, and Karen Shen from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York scoured through mounds of data and found that there is a convincing correlation between increased access to credit and tuition prices at schools. The study used data for higher education (rather than specifically theological education), and it found that between 2007 and 2010 for every $1 increase in loan availability (credit supply), tuition rose by 63 cents. After nuancing the numbers a little, they found the correlation was strongest among private 4-year colleges—the group most similar to seminaries.

Finally, we found that courses on personal finance increased a student’s understanding of debt and that education must happen before loan acceptance in order for it to have an impact on borrowing. While both of these realities seem to be common sense, our post last week revealed that no schools in our study required such courses in their curriculum.

So to recap, what we know thus far: 1) Educational debt is not correlated to the price of tuition; 2) We have created a system wherein students can borrow significant levels of funds each year regardless of how much they are actually paying in tuition; 3) The increased levels of credit made available to students through changes in the federal loan program resulted in money passing from the government, through students in the form of debt, and to seminaries; and 4) Education on this topic can positively influence decisions regarding debt.

In our next article, we will look at a few more things we “know” from our research. Whereas this article shared to specific data points, the next will look at inferences that we may be able to make from our research.